Time to Think Differently About Micro Firms

Imagine two businesses. One is a tech start-up that has developed new AI software. Another is a well-established restaurant in a small town serving their local community. Both count as ‘micro’ businesses, yet their needs will be worlds apart, and no single policy could serve them both well.

Micro businesses are often bundled into the wider “SME” category in policymaking, where they can be seen as simply scaled-down versions of larger firms. This view overlooks the enormous diversity and behavioural differences among the micro business population. But crucially, it could mean the UK misses out on unicorn-style success stories.

Typically defined as those with fewer than 10 employees, they account for over 95% of all UK businesses. Yet they are routinely misunderstood and the quality of data on them is poor. They vary enormously by sector, age, and business model and many behave more like households or consumers than corporates. Most are not in formal networks, unlike in France and Germany where Chamber of Commerce registration is mandatory, making them harder to reach.

A clearer understanding of micro firms is particularly important ahead of the UK Government’s Small Business Strategy, expected to be published this month. The strategy is likely to focus on boosting start-ups and scale-ups and providing direct support for firms. But success will depend on recognising that micro businesses face structurally different challenges from larger firms, and that what works for one segment of SMEs will not work for all.

The label ‘micro’ is too low resolution. Even so, the evidence shows that micro firms face very different challenges from larger ones. Surveys by the British Chambers of Commerce Insights Unit[1] find that micro businesses are more likely to be exposed to challenging economic conditions, less able to absorb shocks and price increases, and more constrained in their capacity to plan ahead.

- Business conditions: The BCC’s Quarterly Economic Survey (QES) for Q1 2025 found micro firms were 12 percentage points less likely to report increased sales than medium-sized firms and 16 percentage points more likely to report worsening cash flow. Many micros cite the recent increase in employer NICs as a major source of pressure.

- Trade: BCC surveys have consistently found that micro businesses are significantly less aware of, and less prepared for, changes related to international trade. The Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) with the EU, in particular, has caused substantial disruption for micro exporters. The volume of paperwork required is disproportionately burdensome for these firms, who may be shipping smaller consignments but still face the same administrative and financial demands as larger businesses.

- Digital transition: a BCC survey in 2024 found that only 22% of micro firms had introduced new technologies in the past year, compared to 45% of medium-sized firms. Time and capacity, rather than appetite, were identified as the main barriers.

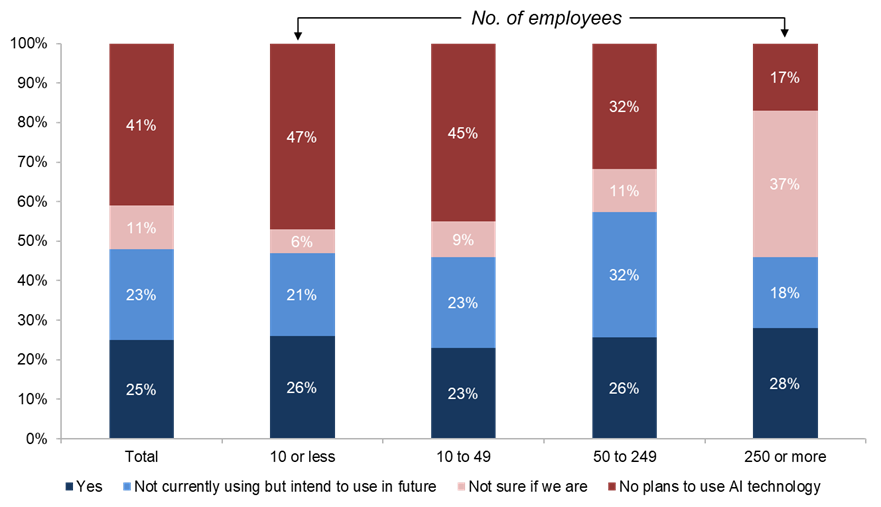

Micros are far more likely to say they have no plans to use AI (though respondents in larger firms are less likely to be sure)

Is your organisation currently using any specific AI technology? BASE: (Total: N = 1187;10 or less: N = 535;10 to 49: N = 342;50 to 249: N = 199;250 or more: N = 111)

But that’s not the whole story. Depending on other characteristics of the micro firm, such as their sector, age, and the personality of their leader, micros can act more nimbly and exude more confidence than their larger counterparts. For instance, while we see tougher trading conditions for micros, we also see in the QES for Q1 2025 that 37% of micro firms expect turnover growth over the next twelve months, compared with 32% of small firms and 28% of medium firms.

Germany is often held as a model for good SME policymaking. Core to this is the “Mittelstand” model, which provides structured support by promoting long-term investment, vocational training, and business specialisation. Over 70% of apprenticeships in Germany are delivered through SMEs, including many micros. Micro businesses also benefit from regional clustering, where localised supply chains create shared growth opportunities. Germany also applies an “SME test”[2] to new legislation, ensuring that regulatory impacts on smaller firms are considered from the outset. The OECD has highlighted Germany’s regulatory regime as among the strongest in Europe for reducing administrative burdens. It also estimates that around a fifth of German SMEs are scalers[3].

The Enterprise Research Centre (ERC) has repeatedly flagged evidence gaps regarding micro businesses, especially sole traders who are often underrepresented in both surveys and administrative data. An expert roundtable convened by the ERC and the National Enterprise Network in June[4] brought together researchers, policymakers, and business organisations to examine how these gaps limit effective policymaking. Participants proposed starting with a full audit of existing data to build a clearer, more detailed picture of micro businesses.

As the Government finalises its new strategy, there is a clear opportunity to think more clearly about the realities of micro businesses. This doesn’t necessarily require a separate strategy, but it does call for a more tailored, evidence-based approach that reflects the wide differences across micro firms.

Micro firms often have little in common with one another, let alone larger SMEs or corporates. Most lack the internal capacity or staff to navigate shifting regulatory and tax requirements. Like the wider public, they often don’t understand the bewildering complexity of policy and they don’t closely follow the high volume of announcements that come from all levels of government. Instead, they rely on word of mouth, trusted advisors, or the internet. Soon, AI may even become a more trusted and effective source of advice than any official government support platform.

Policymakers need to grasp how diverse this group really is – how they behave, grow, and consume information. If the aim is to build a more productive and resilient economy, we will need to start with a better grasp of the firms that make up the vast majority of the UK business population.

David Bharier | Head of Research | British Chambers of Commerce

Please note that the views expressed in this blog belong to the authors and do not represent the official view of the

Enterprise Research Centre, its Funders or Advisory Group