Gazelle firms hoover up rural jobs – but ‘superstars’ boost productivity for all

• Enterprise Research Centre study shows higher numbers of fast-growing firms in a region can lead to net loss of jobs, especially in rural areas

• But clusters of companies that combine job growth with productivity gains have a positive impact from ‘spillover’ effects

• Policymakers need to be aware of trade-offs from promoting job and productivity growth at the same time

The UK’s efforts to boost productivity while ironing out regional inequalities in job creation may be fundamentally at odds, according to a study of so-called ‘gazelle’ firms. he findings, based on a study of 6.25m firms over a 17-year period by the Enterprise Research Centre (ERC), shed new light on the spillover effects high-growth firms have on other businesses in their region.

In recent years, policymakers have looked to high-growth firms – dubbed ‘gazelles’ – as a way of tackling the UK’s chronic productivity problem. Despite accounting for less than 5% of businesses, these companies create around half of all new jobs and typically show higher levels of productivity.

But the research shows that high-growth firms should actually be broken down into two distinct camps – a ‘traditional’ group with fast employment growth (20% growth per year over three years, as defined by the OECD) and a separate group of ‘super growth heroes’ that boost their productivity by growing turnover faster than headcount.

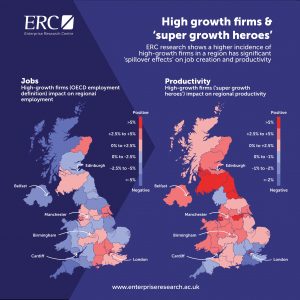

The fast-employment group – spread relatively evenly across the country – was found to hoover up jobs from slower-growing firms in the same region, in what the researchers describe as a “crowding-out competition effect”.

This effect is particularly pronounced in the manufacturing sector and rural parts of the UK, where competition for skilled workers is most intense. A 1% rise in the incidence of high-growth firms in a region was found to cut employment by 0.35% on average – equivalent to a net loss of around 122,000 jobs UK-wide over the period studied (1997-2013). The worst affected regions included the Scottish Highlands, Cheshire, North-east England, Lincolnshire and Devon. In contrast, many urban areas in the South-east and Midlands saw a net jobs gain.

The researchers say a key reason for this could be “labour poaching”, where more go-ahead firms attract the most skilled workers, leaving other firms in an area having to pay their remaining staff more to keep them, further dampening productivity gains. This is likely to be linked to critical skills shortages in some industries.

But the study also found that a 1% rise in the proportion of ‘super growth heroes’ locally boosted productivity of all manufacturing firms in that region by 1.5%, thought to be due to skills and knowledge permeating across supply chains and tighter market competition. This effect was strongest in central Scotland, Inner London, Northern Ireland, Wales and the West Midlands.

Looking at professional services firms (such as those in IT, legal, accounting, engineering, and business administration), however, a higher proportion of ‘super growth heroes’ regionally actually led to a drop in productivity of 5.6% for other firms in the same region – thought to be due to a shortage of in-demand skills.

The study by Professor Jun Du of Aston University and Dr Enrico Vanino of the London School of Economics tracked the experiences of 6.25m firms over a 17-year period. The researchers focused their attention on the 1m manufacturing and professional services firms that experienced an episode of fast growth.

Professor Jun Du said:

“This research shows that the policy goals of job creation and productivity growth are not always complementary at the regional and sector level.

“With the government’s industrial strategy seeking to rebalance the UK economy, policymakers nationally and locally need to be mindful that while encouraging clusters of fast-growth firms can bring productivity benefits to whole supply chains, some regions and industries with acute skills shortages could see unintended consequences.

“We see this particularly in parts of Britain that are distant from major urban centres, with a hollowing-out effect when it comes to net job creation, underlining the need for place-based growth strategies that take account of local circumstances.”

The ERC has also published new research showing how HGFs operate over the long term. A key finding is that most ‘gazelles’ experience episodes of high growth that can tail off over time, with some seeing their growth rates fall to below the HGF threshold and even below that of firms considered non-HGFs.

Lead researcher, Professor Mark Hart, said policymakers needed to be careful not to over-focus on trying to ‘create’ HGFs, but on learning from their experiences as businesses to understand firm growth better.

1. Infographic

2. Full reports:

https://www.enterpriseresearch.ac.uk/publications/fast-growth-firms-wider-economic-impact-uk-evidence-research-paper-no-73/

https://www.enterpriseresearch.ac.uk/publications/fecundity-fertility-survival-growth-research-paper-no-74/

About the Enterprise Research Centre

ERC is the UK’s leading independent research institute on the drivers behind the growth and productivity of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). It is funded by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), Innovate UK, The Intellectual Property Office (IPO) and the British Business Bank (BBB). ERC is producing the new knowledge around SMEs that will allow us to create a business-friendly environment nationwide, grounded in hard evidence. We want to understand what makes entrepreneurs and firms thrive so we can spread the lessons from best practice and make the UK a more successful economy.The Centre is led by Professors Stephen Roper of Warwick Business School and Mark Hart of Aston University, Birmingham. Our senior researchers are world-class academics from both Aston and Warwick Universities as well as from our partner institutions which include Imperial College, Queens University Belfast and the University of Strathclyde.