Business resilience: location, location, location!

Anticipating adversity, and undertaking crisis planning, are associated with increased resilience in businesses. Yet research published earlier this year by the ERC (carried out before the pandemic) found many small firms struggle to identify their most potent future threats and when crisis hits, most have no contingency plans, resorting to depleting their financial resources to tackle it. Investigating SME experiences of crisis, the research found variation by location, and concluded that initiatives designed to help small firms to be more resilient should take this into account. Recent trends highlight that support for SMEs in rural areas should be a particular priority.

The Covid-19 pandemic and resulting lockdowns have had a significant impact on UK businesses during 2020. According to the Bank of England[1], UK businesses reported a fall in sales of around 30 percent during quarter 2, which was largely attributed to the pandemic, and firms are voicing increased uncertainty about future employment and sales prospects, given the unprecedented combination of the ongoing Coronavirus crisis and the imminent end of the Brexit transition period. Even before this perfect storm, ONS statistics indicate that between March and August 2020, the number of employees in the UK on payrolls was down around 673,000[2]. In the light of current circumstances, business resilience – the ability of a firm to rebound, strengthened, from adversity – could hardly be a more topical issue.

An Enterprise Research Centre (ERC) review on the subject of resilience[3] points to a range of firm- and individual-level factors as key to business resilience. These include business models and processes, the adoption of continuity planning and leader and employee characteristics. But the review also found that most resilience research to date has focused on large organisations, rather than SMEs. This is a significant gap in knowledge when you consider that SMEs account for 99.8% of businesses, 66.4% of jobs and 56.8% of value added in the EU[4].

The ERC led a two-year, five-country study into resilience in SMEs[5] in five European cities (London, Paris, Madrid, Milan and Frankfurt), exploring SME experiences of, and responses to, crises. Overall, 31 per cent of the sample of 2,975 firms across the five cities had experienced a crisis which threatened the survival of their business in the preceding five years. Yet the top causes of crises experienced differed from the top risks that firm leaders had identified in all cities, suggesting that leaders of SMEs struggle to identify the most potent threats to their businesses.

Tapping into financial reserves and taking advice from friends and family were the most common ways to deal with crisis in the ERC study, but worryingly, looking at the current context, 42% of UK firms surveyed by the ONS during October 2020 said they had less than six months’ cash reserves and 3% said they had none at all[6].

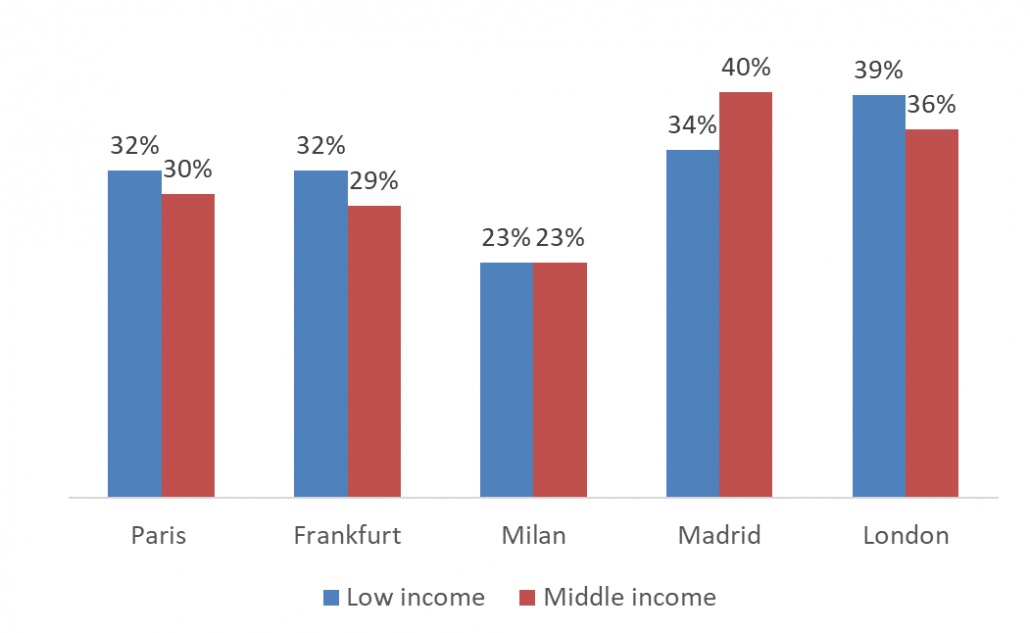

Our research also identified regional differences. In London, Frankfurt and Paris, firms located in low-income boroughs were more likely to have experienced a crisis than those based in middle-income boroughs (see Figure 1). The research concluded that entrepreneurs would benefit from more effective systems for accessing support, and that responsive, locally-informed approaches were required to take account of city and firm differences.

Figure 1: Firms that had experienced a crisis in the preceding five years by borough type and city

Among other things, these findings underline the connection between location and the resilience of firms. However, our research focused on the urban context, but very little is known about business resilience in non-urban environments. This is a surprising gap when you consider that in England, for example, the rural economy accounts for 24 per cent of all registered businesses, 13 per cent of all those employed by registered businesses and nearly 16 per cent% of value added[7].

In fact, there are proportionately more SMEs in UK rural areas than in urban areas, and 71 per cent of people employed by rural registered businesses are employed in SMEs compared to 41 per cent employed by registered urban businesses[8]. This means that the ability of SMEs in rural locations to rebound from crises will have significant implications, for jobs and for economies. Rural enterprises are more likely to be in sectors like production and construction, transport, retail and food, and accommodation sectors than urban firms[9], which are slightly more focused on business and other services. This suggests that in rural areas, failure of a small business may potentially have implications for the provision of key services in their communities. Given the relative importance of SMEs for rural areas, paying attention to the rural context when developing and delivering programmes to increase resilience will be vital.

As Brexit approaches and Covid-19 continues, understanding how to shock-proof businesses will remain at the top of the agenda for policymakers and practitioners alike. Understanding the particular challenges that SMEs in non-urban locations face, and incorporating this knowledge into programme development, could make all the difference for the rural communities these businesses serve. This is one of a number of issues being considered by the newly-launched National Innovation Centre for Rural Innovation (NICRE), which undertakes research and knowledge exchange to inform policy, foster the innovation and resilience of rural businesses, and unlock the potential of rural economies across the UK. NICRE is a collaboration between the ERC, the Centre for Rural Economy and Newcastle University Business School, and the Countryside and Community Research Institute at Gloucestershire and Royal Agricultural Universities.

Maria Wishart, Research Fellow , ERC

Please note that the views expressed in this blog belong to the individual blogger and do not represent the official view of the

Enterprise Research Centre, its Funders or Advisory Group