Firm-level data hints at “canary in the mine” for UK’s employment ‘miracle’

Firm-level data hints at “canary in the mine” for UK’s employment ‘miracle’

• Enterprise Research Centre study finds established firms are already shedding jobs, despite employment being buoyed by start-ups

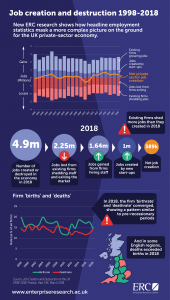

• ‘Churn’ in private sector saw 4.9m jobs created and destroyed last year

• Strong employment figures may be “lulling policymakers into a false sense of security” on economy

Firm-level data on jobs ‘churn’ among the UK’s businesses show early warning signs of an economic slowdown despite the country’s record employment, a new study suggests. The newly-available ONS data, analysed by academics at the Enterprise Research Centre, shows that existing employer-enterprises have seen a faster net loss of jobs in the past two years, only offset by stable but flatlining numbers created by new start-ups.

The ERC has warned that, with around half of start-ups failing within their first year – and firm ‘deaths’ converging with ‘births’ – the UK’s record levels of employment mask a more complex picture of business dynamism on the ground which more closely matches pre-recessionary periods.The researchers looked at data for the period 1998-2018 from the Business Structure Database (BSD) compiled by the ONS.

By totalling new jobs created by start-ups and existing companies as well as jobs lost by firms shedding staff or ceasing to employ workers at all, the researchers established the reallocation rate or ‘churn’ among firms each year for the past two decades. In 2018 alone this totalled 4.9m jobs – equivalent to 23% of all private sector employees changing jobs through hiring and firing.

Existing companies created 1.65m jobs in that year, but this was outweighed by the combined 2.25m job losses from established firms and companies that exited – the highest number since 2010. The net loss of 613,000 jobs from pre-existing firms was only compensated for by around 1m new jobs created by start-ups, giving a net positive figure of just under 400,000.

The total number of jobs lost in 2018 was 17% higher than the previous year, when 525,000 were shed.

Looking at overall numbers of individual firms, the data also shows that the rate of firm ‘births’ has slowed, while ‘deaths’ have risen since 2016, with the two rates now almost equal. In periods of strong economic growth, the firm ‘birthrate’ is typically higher than the ‘deathrate’. But this relationship is reversed in periods of recession. The last time business deaths exceeded births was in 2010-11, towards the end of the Great Recession triggered by the financial crisis of 2008.

And in some English regions – including Yorkshire and the Humber, the East of England and the South West, firm ‘deaths’ actually exceeded new ‘births’ in 2018.

Mark Hart, Professor of Entrepreneurship at Aston Business School, said:

“Firm-level data can be a useful ‘canary in the mine’ for an impending economic downturn and this is particularly significant in the context of record employment figures which could lull policymakers into a false sense of security.

“There is an underlying level of turbulence in the private sector in periods of growth in the economy and this is an important indicator of business dynamism. So the faltering level of job creation from business entry and the rise in job losses in existing firms and though business-exit should be seen as early signs of concern, especially in the current economic climate.

“What’s clear is that established firms are already recording a net loss of jobs. So even if our headline employment figures are being propped up by start-ups creating new jobs, we are already witnessing a severe slowdown in hiring by the established firms that are vital to the health of our economy.”

Case study: Greg McDonald, Chief Executive of Goodfish Group

The experience of established firms nationwide rings true to Greg McDonald, Chief Executive of injection-moulding firm Goodfish Group, headquartered in Cannock near Birmingham and with other sites in Worcester and Loughborough. Since founding the company – which makes plastic components for a wide range of sectors including retail, automotive, aerospace and healthcare – in 2010, Mr McDonald has grown the firm’s headcount from around 30 to 125 through a string of acquisitions, with a turnover of £11.5m. But in the past 24 months, despite taking on 56 new employees the firm has seen a net reduction in staff numbers as 65 left the firm.

While part of this stems from the nature of acquiring firms with disproportionately high staff costs, Mr McDonald says the near full-employment nationally is making it increasingly difficult to hire skilled, motivated workers. Brexit has also become a factor. Goodfish has established a subsidiary in Slovakia, an emerging centre of automotive production in continental Europe, and is waiting on the outcome of the political deal around the UK’s departure from the EU before signing a lease on a new facility, which it hopes to be manufacturing from within six months.

“My mindset as a business-owner is that having all my eggs in Brexitland isn’t a long-term strategy anymore,” said Mr McDonald. “Whatever happens will, over the longer term, put a cap on job creation in the UK and some of that will be diverted to Central and Eastern Europe.”

He has also seen a number of foreign-owned firms selling off their UK manufacturing facilities and believes this indicates the high-water mark of overseas investment in British factories may have passed. “You might see some onshoring or re-shoring, but actually the ownership of manufacturing in the UK has already been capped,” he said. “Business people don’t wait for politicians to make up their minds about how things are going to turn out.”

Policymakers could encourage smaller firms to grow staff numbers by reducing the burden of PAYE and national insurance contributions for younger companies, Mr McDonald said – as well as addressing the high up-front rental fees demanded by landlords on leased premises. “Basically to help an economy to grow, you want start-ups to be able to scale up,” he added. “Big companies tend to constantly reduce employees to increase productivity, whereas scale-ups are trying to build a business and whatever you can do to make that easier has got to help.”

ENDS

Notes to editors

1. Infographic

2. Video

To view a video explainer of the research featuring Professor Mark Hart of Aston Business School, click here

3. Full report

For a copy of the full research paper, Job Creation and Destruction in the UK (1998-2018) click here

About the Enterprise Research Centre

ERC is the UK’s leading independent research institute on the drivers behind the growth and productivity of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). It is funded by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), Innovate UK, The Intellectual Property Office (IPO) and the British Business Bank (BBB).

ERC is producing the new knowledge around SMEs that will allow us to create a business-friendly environment nationwide, grounded in hard evidence. We want to understand what makes entrepreneurs and firms thrive so we can spread the lessons from best practice and make the UK a more successful economy.

The Centre is led by Professors Stephen Roper of Warwick Business School and Mark Hart of Aston University, Birmingham. Our senior researchers are world-class academics from both Aston and Warwick Universities as well as from our partner institutions which include Imperial College, Queens University Belfast and the University of Strathclyde.