Turbulent Times – Business as Usual: 4.5 million jobs created or destroyed in 12 months!

As the tortuously complex process of the UK’s departure from the EU takes another twist, Britain’s economy presents us with a deceptively simple conundrum.

Yes, we have had record headline jobs growth in recent years coupled with falling unemployment. There are, however, widespread concerns about the quality of those jobs caused by the growing ‘gig economy’. And we now have the weekly round of headlines predicting – with varying degrees or indeed zero reliability – the thousands of job losses that will ensue due to whatever type of Brexit deal is finally negotiated.

Such headlines need to be understood in the context of the general pattern of job gains and losses in the economy. The fact is, businesses are hiring and firing all the time. But it is the ‘normality’ of the scale of those actions which often goes unreported – in both good times and bad.

An examination of the UK business stock in the private sector between 1998 and 2017 reveals key trends in job creation and destruction. These data help us to understand the degree of ‘normality’ in the level of turbulence in jobs in the private sector. Using employee data for all employer businesses in the UK, the Enterprise Research Centre (ERC) has examined the average annual job creation and destruction rates between 1998 and 2017[1].

- Job creation can be broadly defined as the positive gross change in employment, summed over all businesses that expand or start up between two points in time.

- Likewise, job destruction is the negative gross change in employment summed over all businesses that contract or close between two points in time.

- Job reallocation rates show the sum of job creation and destruction to provide an indication of the degree to which jobs are ‘reshuffled’ across business ‘locations’ in any 12 month period.

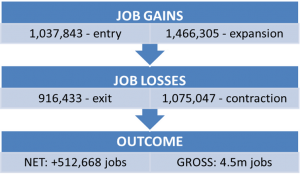

What do we observe in the UK? Our analysis of the process of job creation and destruction shows that 4.5 million jobs in the UK were either created or destroyed in 2016-17. That means that just over a fifth (22%) of all jobs in the private sector were either destroyed or created over the most recent 12 month period – a remarkable level of turbulence in the UK economy, or so it would appear.

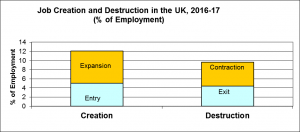

The process is summarized for the 2016-17 period in the following two graphics (Figures 1 & 2).

Figure 1: Job Gains and Losses in the UK, 2016-17 by Component

Source: ONS Business Structure Database (1998-2017)

Figure 2: Job Gains and Losses in the UK, 2016-17 by Component

Source: ONS Business Structure Database (1998-2017)

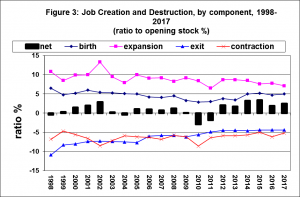

However, from the annual data on job creation and destruction (Figure 3) we can, in fact, see that there was very little variation in these rates of job creation and destruction over the period – averaging around 20-28% over 20 years.

- The Great Recession reduced job creation through entry and expansion, but what is very noticeable is the steady decline since the turn of the century in the amount of job creation through the expansion of existing businesses – a challenge recognised by the recent Industrial Strategy White Paper.

- Job creation through start-ups, however, has been on the rise since the economic downturn.

- Job destruction through exit and contraction have been falling steadily since 2010 and are much lower now than they were 20 years ago.

Figure 3: Job Creation and Destruction, by component, 1998-2017 (ratio to opening stock %)

Source: ONS Business Structure Database (1998-2017)

Final Comments

So, the point is, one needs to be very careful in disentangling any so-called ‘Brexit effects’ in the months and years ahead from such ‘normal’ large-scale turbulence in the hiring and firing practices of UK businesses. How many of the economic forecasting models or the real or imagined sector impact studies of the effects of Brexit actually grasp this level of job churn in their underlying base assumptions on the future performance of the UK economy? A question to occupy our winter work programme and musings in the Enterprise Research Centre as we delve into the data and further examine how this varies by firm size, business age, sector and region – and, dare I say it, in this week of Brexit brinkmanship, which includes our future land border region with the EU27.

Professor Mark Hart, Deputy Director, Enterprise Research Centre

[1] For a detailed discussion of the methodology we employ see Davis et al., (1996) Job Creation and Destruction, MIT Press: Cambridge Mass.

Please note that the views expressed in this blog belong to the individual blogger and do not represent the official view of the Enterprise Research Centre, its Funders or Advisory Group.